Leaving the tenement: an interview with photographer Vaune Trachtman

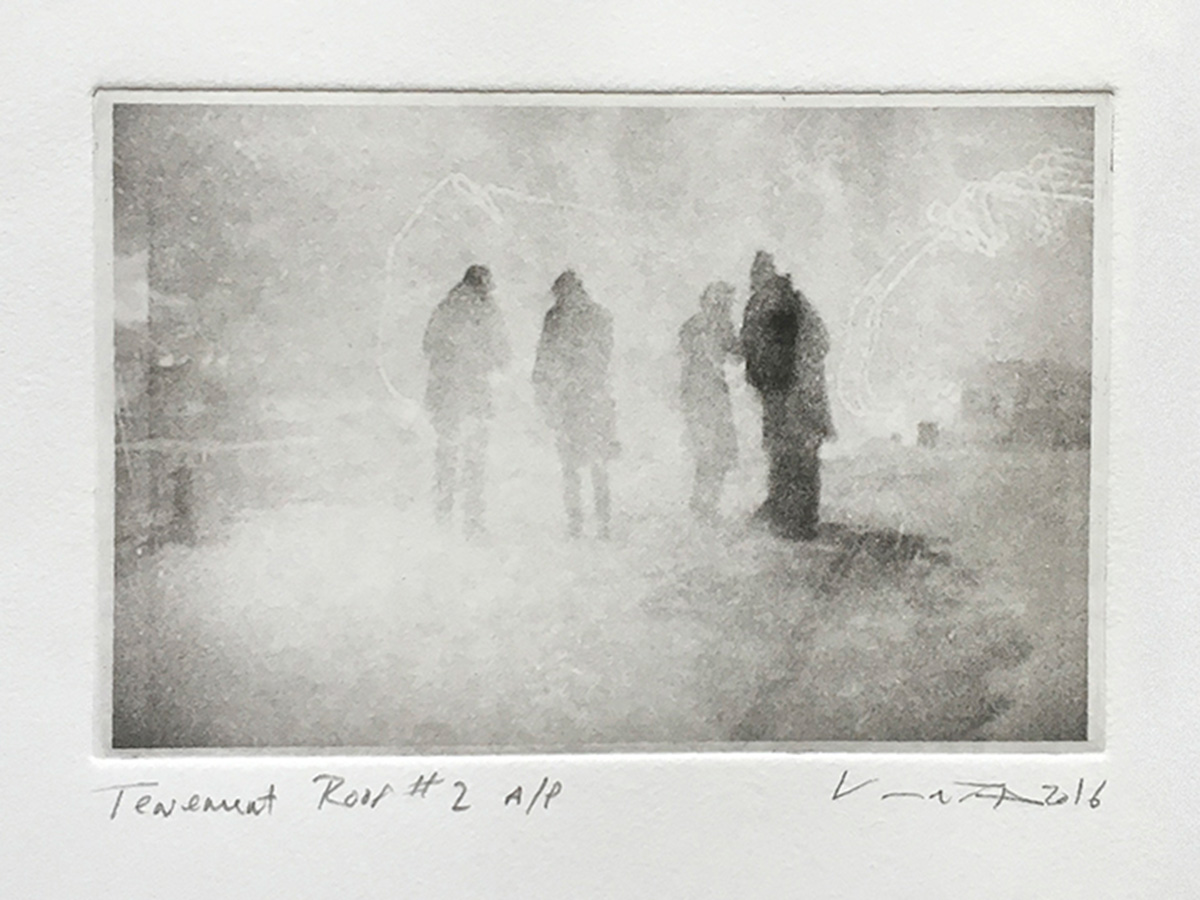

The gasps came from somewhere behind me.I said the words. I said Paul Taylor.And someone connected to these words. We were introducing ourselves at the Making Art Safely Direct-to-plate solarplate workshop, and I mentioned a workshop I had taken with Paul Taylor at Renaissance Press in New Hampshire. We spoke about this for a few moments and moved on to the next participant – the woman who had made the surprised sound to my printmaking revelation.This was Vermont photographer Vaune Trachtman, who has an incredible background in photography. Turns out she worked with Paul at his press. And this is when I knew she was a formidable printmaker (the "Tenement" series she created during the workshop only proved this correct). And she could tell a great story.They say at workshops you learn something from all the other participants, and Vaune was no exception. She taught me some printmaking habits to adopt, like not holding the plate in one hand to clean the edges. Instead you let one side hang off the edge of the table where you inked it, and wipe those free edges and underneath off thoroughly. It’s much cleaner than, well, holding it against your stomach all catawampus. She also provided me with a lot of pointers about Photoshop.And I should mention I am solitary in some things – often printmaking. The whole communal thing is strange. Timing and neatness are a problem. At one point I ended up taking someone else’s heat for an inky fingerprint gracing a piece of printmaking paper (all the papers at this point had fingerprints – but it was my first print, so the plate was not fully charged with ink). Normally I own up to this sort of thing since it is true I am an ink magnet and no matter how neat I try to be, the only way to progress is slowly and methodically. But this time, I did not do it. But I digress.So, we all worked together and were respectful of one another, but the real printing joy happened after class ended, but before the studio closed for the evening. At one point it was just me and Vaune, and I learned the joys and pleasantries of what it is like to work alongside another printmaker.And you know how this goes – L.S. connects with someone, so she is compelled to interview her.So good without further ado:[gallery type="slideshow" size="full" ids="342,344,345,346,343,348,349,350,359,358"]© 2016. Vaune Trachtman

The gasps came from somewhere behind me.I said the words. I said Paul Taylor.And someone connected to these words. We were introducing ourselves at the Making Art Safely Direct-to-plate solarplate workshop, and I mentioned a workshop I had taken with Paul Taylor at Renaissance Press in New Hampshire. We spoke about this for a few moments and moved on to the next participant – the woman who had made the surprised sound to my printmaking revelation.This was Vermont photographer Vaune Trachtman, who has an incredible background in photography. Turns out she worked with Paul at his press. And this is when I knew she was a formidable printmaker (the "Tenement" series she created during the workshop only proved this correct). And she could tell a great story.They say at workshops you learn something from all the other participants, and Vaune was no exception. She taught me some printmaking habits to adopt, like not holding the plate in one hand to clean the edges. Instead you let one side hang off the edge of the table where you inked it, and wipe those free edges and underneath off thoroughly. It’s much cleaner than, well, holding it against your stomach all catawampus. She also provided me with a lot of pointers about Photoshop.And I should mention I am solitary in some things – often printmaking. The whole communal thing is strange. Timing and neatness are a problem. At one point I ended up taking someone else’s heat for an inky fingerprint gracing a piece of printmaking paper (all the papers at this point had fingerprints – but it was my first print, so the plate was not fully charged with ink). Normally I own up to this sort of thing since it is true I am an ink magnet and no matter how neat I try to be, the only way to progress is slowly and methodically. But this time, I did not do it. But I digress.So, we all worked together and were respectful of one another, but the real printing joy happened after class ended, but before the studio closed for the evening. At one point it was just me and Vaune, and I learned the joys and pleasantries of what it is like to work alongside another printmaker.And you know how this goes – L.S. connects with someone, so she is compelled to interview her.So good without further ado:[gallery type="slideshow" size="full" ids="342,344,345,346,343,348,349,350,359,358"]© 2016. Vaune Trachtman

Vaune's Words:

1. What inspired you to become a photographer?A. When I was a kid I always wanted to be able to grab moments in time; I wanted to be able to kind of put them in a box that I could open later and revisit. I wanted to save pieces of the past. It seemed to me that photography helped to do that. So I saved up my baby-sitting money and bought a camera.2. How did you become involved or become interested in doing photographic printmaking processes?A. After living in Seattle for several years in the early ‘90s, I moved back to Vermont and got a variety of jobs related to photography. One of those jobs involved working as a studio assistant with Paul Taylor at Renaissance Press in New Hampshire. That was my first hands-on experience with photogravures. I was lucky to get a chance to work with Paul – the work that comes out of his studio is truly awesome. Working on photogravures with Paul exposed me to some brilliant photographers and artists.After Paul, I had the good fortune to work in Jon Goodman’s photogravure studio. He is based in Florence, Massachusetts, near Northampton. While at Jon’s press, I was a master printmaker and continued to work on making beautiful photogravures from artists living and past.As you’d expect, I loved the images I worked on. But I also loved the paper they were printed on, and the inks, and the smell of the work. I liked the physical process one has to go through in order to make a print. Inking up a plate and running it through a press– it’s great for my process-oriented mind. To me, printmaking is a wonderful marriage of physical and mental space.Recently, someone gave me a beautiful little Intaglio press and I’ve been wanting to use it and get my hands inky again. I was thrilled to find the Direct-to-Plate process of Photopolymer Gravure. It’s less toxic and uses less water than old school photogravures. I feel the time is right to get that press rolling."The Tenement Series" comes from my first foray into the Direct-to-plate process. Having recently left NYC (after living there for 17 years), I feel a little nostalgic for my old tenement apartment at the top of a six-floor walk-up. I’ll miss that apartment. Six floors was a long walk to get to my apartment door, but it was nice little perch that offered good light and good views of Greenwich Village. I wanted the first images that I made with this new process to be of that place and that time of my life.3. For a long while you had a distinctive career doing photo retouching for magazines. What caused you to chose this photographic career route?A. I was a photo retoucher, also called an Imaging Specialist, for Time Inc. I got my job at Time on summer break while I was in graduate school (I did a dual photo program between New York University and International Center of Photography). At first, I worked in the photo editorial department at Time. Then I left, went back to school, graduated, and returned.I liked being part of Photo Edit. Being around pictures was great for me. Sometimes I would handle the very negatives of world famous images I’d known my whole life. That was amazing. But the fact is that I’m a really process-oriented person and I’m more interested in working on making pictures look good than on setting up assignments. So I set my sights on joining the Imaging Department.Once there, I worked with layouts and color correction and in some instances pixel manipulation (never for documentary images, though). The Imaging Department at Time Inc. works with many different kinds of magazines, far more than just Time. There’s Sports Illustrated, Fortune, This Old House, Life books, and many other publications. I was with Time Inc. from 2000 till 2015, and I feel incredibly fortunate to have been able to see and take part in the huge changes that have occurred in photography as it moves from analog to digital.I learned a lot at Time. I learned not to be afraid of technology. I learned how to play with it, and I learned how I can grow as technological changes come about. In the end it’s all about imaging making– how one takes a three-dimensional vision and puts it on paper. There are a lot of ways one can go about this. There are a lot of good ways to interpret something. There are a lot of good choices to make about how you want something to look.4. You are the only photographer I know who has special privileges at the International Center of Photography (ICP). Granted I am in awe of this, but what is it like to be able to use their print lab and other facilities in your own time and place?A. It’s not really a special privilege. Really, its not.ICP has two functions – the museum/gallery and the school. It’s the school part where I’ve printed. You can use their facilities (digital media lab, darkrooms) by taking workshops and classes. I’ve done that, but I’ve also worked as a teaching assistant, which gives me a time-for-time trade. For example, in exchange for helping in a Photoshop class, I get to use ICP’s printers. This has worked out great for me. As I mentioned, for many years I lived in a small apartment at the top of six flights of stairs (no elevator) and I didn’t have room for a big mural printer. Now that I’ve moved to Vermont full-time and ICP is 200 miles away, I think I may need to come up with another printing option. New York is a long way to go to make a big digital print. Right now, I’m thinking that maybe printmaking and photopolymer gravure will be the printing answer I’m looking for.5. What is the best photo adventure you have had and why?A. Oddly enough, the first thing that comes to mind is about the photo I didn't get.I had just moved to Seattle after graduating from college in Vermont. It was the early 90s and it was the day the Gulf War started. My boyfriend (now husband) and our good friend Jon and I decided to head over to the war protesters on Broadway and Pike. More people had gathered than we anticipated, and there weren't many police around. Things started to get a bit heated. I had just run out of film and there was this one guy all decked out in black military gear– he looked kind of like a motorcycle cop, but all in black. He even had a helmet on. Anyway, he was dancing around with this really big American flag. He was waving it in the air and wrapping it around himself. It wasn’t on a flagpole or anything. It was dusk and he was getting kind of hard to see except for the reflections off of his helmet and dark glasses. Then he lit the flag on fire and it started to burn in a circle from the center of the flag and out to the edges. As it burned he continued to dance in the center of the flag. Boy, I wish I got that picture. I can see it so vividly in my mind’s eye. I hated that I missed getting it. Missing that shot makes me look more closely – I don’t want to miss anything like that again.I think it’s a good exercise, to think about the pictures you didn’t take, and why.When I think about adventures that did produce pictures… one of my favorite adventures was on the dance floor at The Rebar in Seattle. My camera was a little Minox that I’d bought at a yard sale at The Pike Place Market. It was so small you had to advance the film twice to get to the next frame. It was my little spy camera, and I used to take hip shots. I used high-speed film that I pushed two stops, and I set the shutter speed at 1/15 of a second. I’d notice how the light crept into the dance floor while people were moving with the music. I’d try to aim my lens at the light, not the shadows. I never brought the camera up to my eye to look through the viewfinder; I just carried my little Minox in my palm and trusted my instincts. It was a fun exercise in timing, movement, observation, and light, all triggered by the rhythm of the music. I got to know that little camera so well that when I held it in my hand, my hand became an extension of my eyes.

To learn more about Vaune’s work visit:

- Website – vaune.net/wp/

- Instagram – www.instagram.com/vaune622